Planning and Managing Distance Education Systems: Complex Systems

Farhad (Fred) Saba, Ph. D.

Founder and Editor, Distance-Educator.com

Over the past 30 years, while designing and implementing distance education systems at different scales, from large enterprises to stand alone courses, it became evident to me that planners and administrators usually base most of their decisions on what type of hardware and software to acquire. Although hardware and software systems are essential for distance education systems, they are not sufficient ingredients. Rarely consideration is given to any of the other components, and stakeholders that comprise a distance education system.

Simply put, planning and implementing distance education programs involve myriad systems ranging from hardware and software that is required for production of instructional and learning systems to telecommunications systems needed to put the learner in touch with the teaching organization, as well as an intricate web of relationships among educators who work in academic and training departments and divisions as well as other organizational units within an institution of higher education, a K-12 school or in a corporation. Furthermore, distance education systems are also subject to rules of societal systems which directly influence important matters, such as, copyright protection or accreditation to name a few. Because distance education programs are offered on the World Wide Web, they are subject to influences of global systems and are also affected by such systems. In short, distance education systems are complex.

In short, distance education systems are complex.

Complex systems are those that have a group of interacting parts that affect each other and are affected by each other. In fact complex systems are not things that we can touch and feel; they consist of interactions and inter-relationships that are not tangible, and that is why they are difficult to define. (Waldorp, 1992, Verma, 1998).

Complexity is present in all educational systems and distance education is no exception. Distance education systems hold a basic characteristic of complex systems, that of hierarchy. According to Ahl and Allen (1996), “Complex systems are defined as those systems which require fine details to be linked to large outcomes. Forging this link in a way that allows predictability requires addressing multiple levels of analysis simultaneously. Examples are as diverse as a telecommunications satellite, or a poem” (p. 11).

An example of such hierarchy in nature is

- Cell

- Organism

- Population

- Community

- Ecosystem

- Landscape

- Biome

- Biosphere (Ahl & Allen, 1996).

To understand distance education in its complexity, plan for it and manage it, requires a model that carefully defines each system component in detail and represent the relationships among its parts in mathematical terms.

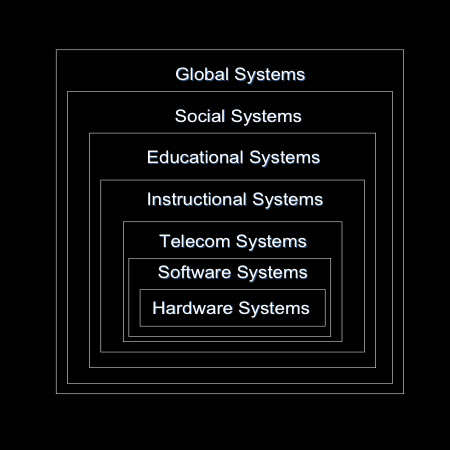

In the early 1970’s, while working on my doctoral degree at Syracuse University, with the guidance of Dr. Guss Root, and Dr. Donald Ely, my dissertation advisers, I developed a hierarchical model of distance education that consisted of seven nested levels. The graphic depicted here shows this model. Each of these system levels is complex in its own right, but relatively and cumulatively, they increase in complexity from the core of the model (Hardware Systems) to the outer layer (Global Systems). As importantly, each system level effects all the others and is affected by all the others.

Over the years, this model has been modified and revised several times to explain the systems theory of distance education (Saba 2007, 2013). Before elaborating on the application of this model to planning and managing, several explanations are necessary:

1- Universities are more complex than the components and processes presented in the above model. Developing more comprehensive models will become necessary if you adopt the hierarchical model of distance education presented here for planning and managing purposes in your organization.

2- Each institution is unique and a general model does not apply to all. The hope is that educators develop models that uniquely represent their organizational structure, work flows, and processes at the current time or for a planned future.

3- One may take many points of view for analyzing system levels in this model. In future articles, I will touch upon their basic characteristics, key personnel that work in them and the possible effects that each level may have on the entire model.

4- The system levels that will be described are for planning and managing purposes.

Complex systems are those that have a group of interacting parts that affect each other and are affected by each other. In fact complex systems are not things that we can touch and feel; they consist of interactions and inter-relationships that are not tangible, and that is why they are difficult to define.

- The hierarchical nature of the model does not imply that one level is more important than the other. They all are equally important for the operation of a distance education enterprise, as one cannot say that the lung is more important for sustaining life in the body than the heart. However, the hierarchy implies that higher level systems influence and even at times control the behavior of the lower level systems.

- There are no clear cut lines of demarcation in these levels as systems are not tangible entities in the mechanical sense where one component ends and the other begins. These levels are systems of influence and at times they overlap and may seem indivisible.

- One of the major characteristics of hierarchical complex systems is that each higher level subsumes the lower levels, and is directly or indirectly affected by other levels. For example, an increase in production of digital cameras (hardware systems) in one country reduces its cost of ownership (societal systems) and influences the production of instructional videos in other countries (global systems).

5- Modeling is a planning process as well. The process, as explained in future articles, is as important as the product (i.e. the model) itself. Therefore, the value of the model is to the extent that it can facilitate the planning effort in your institution.

The hope is that educators develop models that uniquely represent their organizational structure, work flows, and processes at the current time or for a planned future.

With these points in mind, starting next week, I will begin explaining this general model that can be used for identifying important system components in your institution and planning for the relations among them . Inevitably, you will realize that components and relationships may exist in your organization that are not represented in this model. You can add them to your model as it develops.

If you find this model interesting and would like to explore its application to organizing the future of distance education program in your institution, please contact me via email at Saba@distance-educator.com.

REFERENCES

Ahl, V. & Allen, T. H. E. (1966). Hierarchy theory: A vision, vocabulary and epistemology. New York, NY: Columbia University Press

Saba, F. (2013). Building the future: A theoretical perspective. In M. G. Moore (Ed.). The Handbook of distance education, (3rd Ed.) (pp 49-65). New York, NY: Routledge.

Saba, F. (2007). A systems approach to theory building. In M. G. Moore (Ed.). The handbook of distance education, (2nd Ed.) (pp. 43-55). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Saba, F. (1976). The evolution of educational technology in Iranian education. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY.

Verma, N. (1998). Similarities, connections and systems: The search for a new rationality for planning and management. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Waldrop, M. M. (1992). Complexity: The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.